The Longest Day

Today we explore what will later become known as ‘The Longest Day‘ as the Martians, having destroyed those units which had attempted to surround them, begin their move on London. It is today, that 4 Company (Special Operations), Coldstream Guards is deployed, and the first naval engagement of the war occurs.

For Toni, her concerns for @hgwellsbro escalate as refugees begin to appear in London. Her fears for her personal safety begin to conflict with what she sees as her responsibility to help her fellow human beings.

The Curies, unable to return France, are forced to stay with Morant.

And the Martian’s release the black-smoke for the first time with devastating effect.

Notice POSTED at Waterloo Station – “A breakdown in the London & South Western Railway’s line between Byfleet and Woking has required the L&SWR to run it’s theatre trains via Virginia Water or Guildford, rather than through Woking…

The notice continues: “L&SWR are presently making arrangements to alter the route of the Southampton and Portsmouth Sunday League excursions. Further details will be posted when available.”

Telegram from Brigadier-General Marvins, Weybridge, to CinC Field Marshal Wolseley.

“CONFIRMED SIGHTING OF ANOTHER MARTIAN METORITE – THE 4TH STOP”

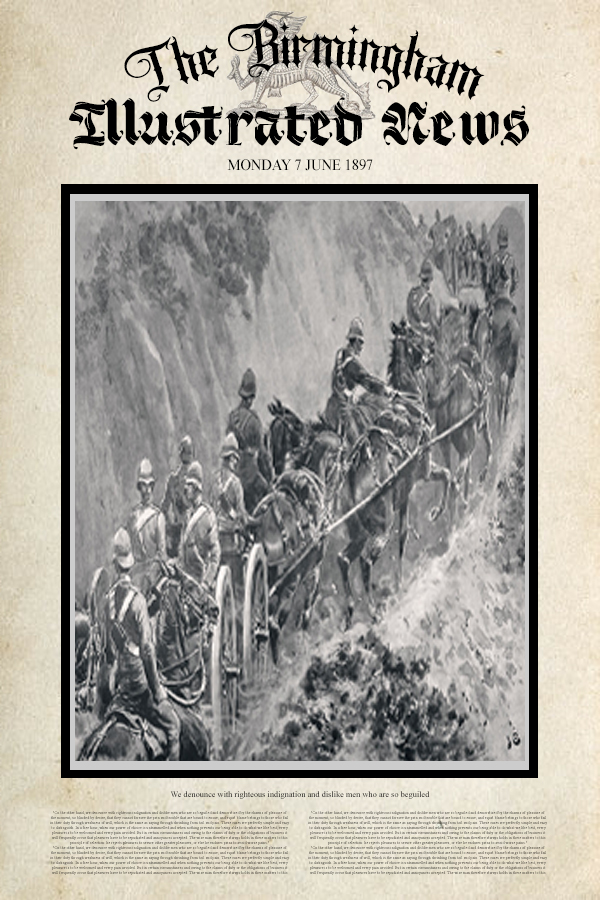

With storm clouds strengthening overhead, the soldiers can see something moving rapidly down the slope of Maybury Hill towards them. A Martian tripod, balanced on 3 elongated legs, higher than many houses. The clattering tumult of its passage mingles with the riot of the thunder.

Wells, who observed the tripod’s passing, described it as “incredibly strange, for it was no mere insensate machine driving on its way. Machine it was, with a ringing metallic pace, and long, flexible, glittering tentacles swinging and rattling about its strange body…

“But it picked its path as it strode along, and the hood that surmounted it moved to and fro as a head looking about. Behind the main body was a huge mass of white metal like a gigantic basket, and puffs of green smoke squirted from the joints of its limbs as it swept by…

“And then it was gone, and I heard its exultant deafening howl, drowning the thunder—”Aloo! aloo!”. Another minute it was with its companion, half a mile away stooping over the third of the cylinders they had fired at us from Mars. And then the storm hid them from my sight.”

Unsigned note prepared for CinC Field Marshal Wolseley:

“All Horshall Common appears on fire. Reports from what remains of the troops remain around the sand pits are of huge black shapes moving busily to and fro within the pits.”

The note was initialled by the CinC at 1:05.

Wells, who observes the massacre, later reports that he was told “that a train had been wrecked near the arch at this time, and that a number of black figures could be seen hurrying one after the other across the line against the light of Woking station.”

Wells speaks to an artillery man, who refused to give him his name at that time. The artillery man, who was involved in the debacle at Woking claimed the Martian’s simply wiped them out.

Just my luck, we’re at war and my command has been ordered in the opposite direction to the enemy – Kilvaney gets all the luck.

Train network is a real mess, took us 5 hours to get to Tilbury, arrived 02:00, only to find that no-one had told the Fort we were coming. Took an hour to get both platoons transferred to the Fort.

I hate Mondays.

Wells is still in the company of the artillery man as the sun finally rises over a scene of utter devastation, and now watches as the artilleryman (who has been directed to report to Brigadier-General Marvins at Weybridge) heads off.

Wells, after observing the massacre, now decides to return to London via Leatherhead (where he’d left his wife) and latter recounts meeting a lieutenant and a couple of privates of the 8th Hussars, about half a mile from the Common.

Both the The Birmingham Illustrated News (BIN), and its older, sister publication The Illustrated London News (ILN), both normally weeklies, brought out a special edition. Founded by Herbert Ingram, the ILN had first appeared in 1842. the BIN several decades later.

The BIN leads with: “At 7pm last night the Martians came out of their cylinder, and under the armor of metallic shields, completely wrecked Woking station, the adjacent houses, and massacred an entire battalion of the Cardigan Regiment…

“Maxims have been absolutely useless against their armor; the field-guns have been disabled by them. Flying hussars have been galloping into Chertsey. The Martians appear to be moving slowly towards Chertsey or Windsor…

“Great anxiety prevails in West Surrey, and earthworks are being thrown up to check the advance Londonwards.”

Feeling more settled this morning after a decent sleep in #QueenAnnesMansions. Ducked out to get the morning paper. #TheSundaySun reports #Martians have completely wrecked #Woking Station!

@hgwellsbro am now almost beside myself. Where are you?

And #TheSundaySun says #Martians have massacred a whole battalion of the #CardiganRegiment! They have #armour, #heatrays, and #tripods! #fear #heartpoundingagain

We are at war with the Martians, but Brown and Vogan agree the threat of a court-marshal means it is unsafe for our health to re-join the regiment.

We are still looking after the Curies. Trains to Dover will not be running anytime soon.

Telegram sent to The Times from their correspondent at Byfleet station reveals that the correspondent had spotted more soldiers at this time, but no signs of the Martians. Byfleet is 4 miles from Woking.

Wells later reports sighting “6 twelve-pounders set up in a field outside Byfleet at this time, pointing towards Woking. The gunners stood motionless by the guns waiting, almost as though ready for inspection. The ammunition wagons at a business-like distance from the guns.”

Wells continues towards Weybridge where, just over the bridge, he sees a number of men in white fatigue jackets throwing up a long rampart, with more guns being emplaced behind.

Byfleet is now a tumult, people packing, and hussars, some of them dismounted, trying to hurry them up. Wells reported seeing “3 or 4 black government wagons, with crosses in white circles, and an old omnibus, being loaded in the village street.”

Weybridge is also in confusion, and grenadiers in white are warning people to move now or to take refuge in their cellars as soon as the firing begins. Despite the urgency, Wells notes that the soldiers are having the greatest difficulty in making people realize the gravity.

From the log of HMS Thunder Child, 07 June 1897 09:19 GMT

Lt. Farmer reports that the ship’s wireless is not working. He is trying to make repairs but remains doubtful, as he believes the cause may be due to some sort of interference with his signal. Ship speed 14 kts. Heading 112 degrees, ESE. Sky clear, seas light, winds calm.

Near Shepperton Lock (near where the Wey and Thames join) people begin forming long queues for the ferry. On the other side of the Thames everything is still quiet, in vivid contrast with the chaos on the Surrey side.

Telegram from Brigadier-General Marvins, Weybridge, to CinC Field Marshal Wolseley.

“ALL BATTERIES HAVE ENGAGED THE ENEMY.”

Wells, waiting for the ferry, later reports seeing: “a haziness over the tree-tops and a sudden rush of smoke far away up the river, and forthwith the ground heaves underfoot and a heavy explosion shakes the air, smashing two or three windows in the houses near, and leaving us astonished…”

Finally Wells sees: “one, two, three, four of the armoured Martians, far away over the little trees, across the flat meadows that stretch towards Chertsey, striding hurriedly towards the river as fast as flying birds…

“And then a fifth. Their armoured bodies glitter in the sun as they sweep swiftly forward upon the guns, growing rapidly larger as they draw nearer. One flourishes a huge case high in the air, and the ghostly, terrible Heat-Ray strikes Chertsey.”

Wells, with others, races for the safety of the water, ignored for the moment by the Martians, even as a tripod breaches the far bank, and is fired on by a hidden battery of 6 guns.

Wells, later records that: “the first shell bursts 6 yards above the hood. Simultaneously 2 shells burst in the air near the body as the hood twists round in time to receive, but not in time to dodge, the fourth shell…

“The fourth shell bursts clean in the face of the Thing. The hood bulges, flashes, and whirls off in a dozen tattered fragments of red flesh and glittering metal. A spontaneous cheer arises from those watching…

“A violent explosion shakes the air, and a spout of water, steam, mud, and shattered metal shoots far up into the sky. And now a huge wave, like a muddy tidal bore, but scaldingly hot, sweeps down the river…

“Thick clouds of steam pours off the wreckage, and the machine’s gigantic limbs churn the water and fling mud and froth into the air. The tentacles sway and strike like living arms. Enormous quantities of a ruddy-brown fluid are spurting up in noisy jets out of the machine…

“The air is full of sound, a deafening and confusing conflict of noises—the clangorous din of the Martians, the crash of falling houses, the thud of trees, fences, sheds, flashing into flame, and the crackling and roaring of fire…

“Dense black smoke leaps up to mingle with the steam from the river, even as the Martian’s Heat-Ray passes to and fro over Weybridge its impact marked by flashes of incandescent white, that change immediately to lurid flames…

Around Wells: “houses cave in as they dissolve at the heat ray’s touch, and darted out flames; the trees changed to fire with a roar. It flickers up and down the towing-path, licking off the people trying to run…

The edge of the Heat-Ray sweeps down to the water’s edge not 50 yards from where Wells stands, before arching across the river to Shepperton, and the water in its track rises in a boiling wheal crested with steam, scalding those still in the water. And then quiet.

In 1899, Well’s published the first edition of The War of the Worlds via a series of serials in the USA. The American publisher included Goble’s illustrations. In the second and subsequent editions (Book II, Chapter 2) in the middle of dealing with a planet blasted by alien war, Wells takes some time to give a bitchy critique of the war reporter’s illustrations:

I recall particularly the illustration of one of the first pamphlets to give a consecutive account of the war. The artist had evidently made a hasty study of one of the fighting-machines, and there his knowledge ended. He presented them as tilted, stiff tripods, without either flexibility or subtlety, and with an altogether misleading monotony of effect.

The pamphlet containing these renderings had a considerable vogue, and I mention them here simply to warn the reader against the impression they may have created. They were no more like the Martians I saw in action than a Dutch doll is like a human being. To my mind, the pamphlet would have been much better without them.

Telegram from Brigadier-General Marvins, Weybridge, to CinC Field Marshal Wolseley.

“DESPITE A HEAVY LOSS OF TROOPS ONE MARTIAN HAS BEEN DESTROYED AND THE OTHERS HAVE FALLEN BACK TO THEIR ORIGINAL POSITION UPON HORSELL COMMON STOP”

Wells, who had observed the destruction of the single Martian, and suffered serious scalding to both hands, is now heading towards London.

#Refugees from further west have begun to appear in #London. @graceharwoodstewart and I have been handing out water and directing them towards @NUWSS stations. Currently on short break to #refuelourselves

From the log of HMS Thunder Child, 07 June 1897 13:01 GMT

Off the coast near Shearness. Observed black smoke arising from coast. Captain orders speed slowed to 5 knots and a change of course to investigate. Heading now NNW Low overcast, winds westerly. 10 mph some chop at sea. Colossus follows astern.

From the log of HMS Thunder Child, 07 June 1897 13:22 GMT

Drawing closer to coast. Now off Sheerness. Can plainly see with aide of binoculars waterfront aflame and populace crowding the wharf into small boats and making for open water. Lookout reports large metallic tower-like structure rising over the docks. Conditions as observed earlier: layer of black low-lying smoke now heavier close to shore.

From the personal log of Lt. Roger Carver, #RoyalMarines HMS Thunder Child, 07 June 1897 13:25 GMT

I raised my glasses and stared wordlessly at the gleaming apparition rising over the town.

It towered above the steeple of the nearby church on three separate but flexible legs, a hooded carapace at its apex. Calmly and deliberately, like a young boy quashing an anthill, it pushed itself into the steeple, sending it clanging to the ground. “What in the hell is that?”

“That, Mr. Carver,” said Captain Allenby, focusing his binoculars, “is the enemy. Sound action stations.”

From the personal log of Lt. Roger Carver, #RoyalMarines HMS Thunder Child, 07 June 1897 13:26 GMT

“Open fire.” The deck shook under my feet as our twin twelve-inch guns in our fore and aft turrets flashed and roared. I watched as the shells exploded around the Martian fighting machine, kicking up plumes off dirt and debris. “Get your shells on target, if you please,” said Allenby, intently watching the shoreline through his glasses from the wing of the bridge.

From the log of HMS Thunder Child, 07 June 1897 13:30 GMT

Captain orders action stations at 13:25 hrs. All guns manned and report ready. Main A and B turrets brought to bear against enemy. Captain orders flag hoist to Colossus: Will engage enemy machine in town. Captain orders open fire.

From the personal log of Lt. Roger Carver, #RoyalMarines HMS Thunder Child, 07 June 1897 13:40 GMT

I looked fore across the bow to where Colossus had taken up position, some 100 yards from us. Our sister ship had swung aimed its main battery ashore and fired on a second Martian fighting machine that appeared in the town. Colossus’ gunners, by chance or design, had straddled the second Martian with their first round, which seemed to get their notice.

From the personal log of Lt. Roger Carver, #RoyalMarines HMS Thunder Child, 07 June 1897 13:44 GMT

“Closer, but not quite,” said the captain, lowering his glasses.

“Look!” shouted Mr. Farmer, pointing.

We turned to watch one of the enemy fighting-machines step out from the town, across the stony beach and wade into the water towards us, as to challenge our position. The small boats that were the harbour scattered in every direction trying to get away. Colossus must’ve seen it too, as we watched it’s the barrels of its main batteries depress further as the turrets swung to get a bearing.

“Hard a port!’ yelled Allenby from the bridge wing. “Now!” He cupped his hands as he rasped into the speaking tube. “All batteries fire.” I felt the Thunder Child lurch suddenly and grabbed a rail with both hands, as the ship struggled to bring the full weight of her broadside to bear on the enemy.

From the log of HMS Thunder Child, 07 June 1897 13:45 GMT

Look out reports HMS Colossus has taken enemy fighting machine under fire.

From the personal log of Lt. Roger Carver, #RoyalMarines HMS Thunder Child, 07 June 1897 13:55 GMT

I watched as the Colossus’s broadside erupt in fire and fury. Four twelve-inch shells arched out and struck the lead enemy fighting-machine, causing its carapace to detonate in a ball of fire. A great cheer went up from the bridge as the tripod reeled as if punched in the face and fell back into the water with a splash.

“Now that’s shooting,” smiled Captain Allenby, lowering his glasses.

From the personal log of Lt. Roger Carver, #RoyalMarines HMS Thunder Child, 07 June 1897 13:57 GMT

Our exaltation was short-lived. The surviving fighting-machine rose it is full height and from it rose an almost mournful cry of, “Ulla! Ulla!” that boomed out over voices, drowning us out into shocked silence.

From the log of HMS Thunder Child, 07 June 1897 14:01 GMT

Look out reports a second Martian machine standing on the shoreline.

From the personal log of Lt. Roger Carver, #RoyalMarines HMS Thunder Child, 07 June 1897 14:02 GMT

I cursed under my breath as I saw the new fighting-machine on the shoreline. The people left on the nearby pier saw it too; through my glasses I could see them push each other towards the already overcrowded small craft, shoving some hapless individuals into the water, their arms windmilling as they went. The fighting machine extended a long black tube and directed at the masses at the pier.

From the log of HMS Thunder Child, 07 June 1897 14:03 GMT

Look out reports the second Martian machine producing what appears to be smokescreen from a long black tube and projecting towards the people on the pier. Smoke is black, heavy and lays close to the water.

From the personal log of Lt. Roger Carver, #RoyalMarines HMS Thunder Child, 07 June 1897 14:04 GMT

I could hear the screams of the people crowded on the pier echo across the water as the black smoke fell on them. They cried in terror, trying to escape, some even jumped into the water. As the smoke covered them, their voices began to choke out.

My mouth hung open.

From the log of HMS Thunder Child, 07 June 1897 14:05 GMT

Look out reports black smoke clearing from the pier. Reports no-one left alive.

From the personal log of Lt. Roger Carver, #RoyalMarines HMS Thunder Child, 07 June 1897 14:06 GMT

I lowered my binoculars. “It murdered them wholesale.”

“No, Carver,” said Mr. Farmer, bitterly. “That would require an acceptance of equality between us. It’s an extermination. That’s what it is. Like a farmer would poison an infestation of vermin.”

From the personal log of Lt. Roger Carver, #RoyalMarines HMS Thunder Child, 07 June 1897 14:07 GMT

All eyes were on the second now Martian now, as it raised a camera-like apparatus with a circular mirror and directed it towards the victorious Colossus. It flashed and stabbed out, knife-like at the beating heart of the battleship. The Colossus erupted in fire and steam as it was sundered from bow to stern by the invisible blade.

From the log of HMS Thunder Child, 07 June 1897 14:08 GMT

HMS Colossus destroyed by enemy action.

From the personal log of Lt. Roger Carver, #RoyalMarines HMS Thunder Child, 07 June 1897 14:09 GMT

“My God in heaven,” Allenby lowered his glasses as he watched the expanding column of smoke and steam arise from the sinking pyre of the Colossus. He turned back and called out, “All batteries fire! Fire as you bear!” The ship rocked as our main batteries engaged the enemy.

The smoke cleared. To our immense encouragement, we had hit the second fighting-machine, damaging it in its rearmost leg with a glancing blow. It limped away from us, almost painfully pulling its injured leg with the remaining two, towards the safety of its partner, calling out, “Ulla! Ulla!”

From the log of HMS Thunder Child, 07 June 1897 14:11 GMT

Scored hit on enemy fighting-machine, damaging it, with fire from forward turret. We are closing the distance.

From the personal log of Lt. Roger Carver, #RoyalMarines HMS Thunder Child, 07 June 1897 14:12 GMT

We are rapidly closing the range between us and the injured Martian. The captain’s aim had been to destroy it before it could receive aid from its companion advancing from the shoreline. However, that point was already moot: the Martian had already joined its stricken partner. It extended its long black tube and began to produce the same thick, low-hanging black smoke that had exterminated the hapless townsfolk.

From the log of HMS Thunder Child, 07 June 1897 14:13 GMT

Second fighting-machine producing stream of black smoke.

From the personal log of Lt. Roger Carver, Royal Marines, HMS Thunder Child, 07 June 1897 14:14 GMT

For a fleeting instant, I thought the captain mad enough to pierce the black wall of swirling smoke that was drifting towards us with the ship and ram the Martian. But then, I heard him call out from the wing of the bridge, “Hard starboard! All engines full ahead.”

I gripped the railing and exhaled in relief. I heard the clang of the engine telegraph and could feel the ship begin to heel to the right as she began her turn. The smoke would miss us.

From the log of HMS Thunder Child, 07 June 1897 14:15 GMT

Thunder Child breaks contact with enemy.

From the personal log of Lt. Roger Carver, #RoyalMarines HMS Thunder Child, 07 June 1897 14:30 GMT

We were rapidly retreating from the enemy. There was no putting a brave face on it. I looked at the captain. He stood silently on the bridge looking out to sea, his faced fixed in a frown. Our ship – the Thunder Child – was the pride of the Royal Navy and the Empire. A marvel of the modern age. I looked back at the cloud of black smoke astern us that now smothered the coast. But what could we do against that?