Eulogy for the Fallen

From a historical perspective, we are beginning to see that determination, organisation, and competence, lead to results that have far reaching consequences. As does the opposite.

We continue to see the @NUWSS’ organisational abilities with outposts now in regular contact now via radio. In her diary Toni notes the increasing difficulty of moving through London because of the Red Weed which has clogged London’s waterways and caused the Thames to break its banks.

In Woking we witness the determined assault on the Martian’s pit, while in London Morant delivers the eulogy for Pierre Currie at a small commemoration service held in the undercroft at Westminster.

From the personal log of Lt Roger Carver, Royal Marines, HMS Thunder Child, 20 June 1897, 07:30 GMT:

‘You’re sure now, sir?” Sergeant Howard regarded Maxim’s flying machine and its long catapult track with scepticism.

“I’m not,” I said, “but if there’s a chance that it’ll work, I need to be here. I trust you and Lieutenant Mann have deployed per my orders?”

“Yes, sir.”

“Carry on then, Sergeant -Major Howard,” I saluted and shook his hand. “And take care of yourself.”

“You too, sir. And don’t worry about Mr. Farmer, sir. We’ll keep an eye out for him.”

“Very good, Sergeant. Don’t be tardy.”

“I wouldn’t miss it for the world, sir.” Howard smiled.

From the personal journal of Hiram Maxim

I was still not well enough to pilot my machine. Reluctantly, I would leave that to Mr Carver and Persephone. I was with the crew of the 12-pounder, overlooking Horsell Common. I pulled out my pocket watch. My head still hurt. But no matter: it would not be long now.

The men were dug into a slit trench anchored at each end by a Maxim gun, one hundred yards ahead of us, almost at the crater’s rim. The men dug the trench with the greatest of care and bravery over the last two evenings as to not be discovered by the Martians. No sign of Farmer.

From the personal log of Lt Roger Carver, Royal Marines, HMS Thunder Child, 20 June 1897, 07:52 GMT:

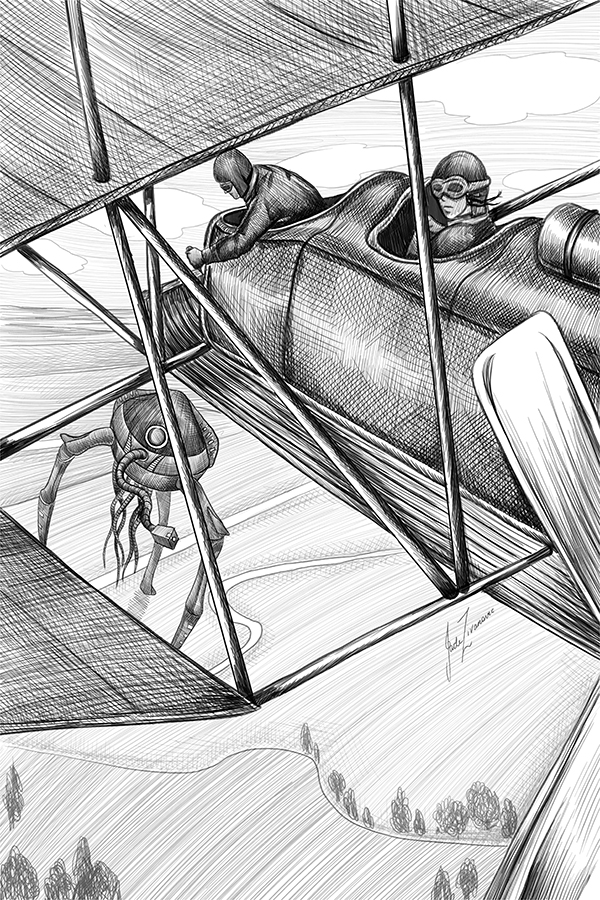

I sat strapped into the bow of the Maxim’s flying craft. Persephone sat behind me her hands gripping the tiller. Occasionally, she would make an adjustment to the throttle lever, causing the giant steam engine driving a four-bladed airscrew to thunder and shake the machine.

I carried a bag of dart-like grenades in my lap that I were to drop on the enemy when we passed over. The machine shook around us, its engine at full power, restrained on the catapult track by the locking mechanisms. “Ready to go?” Persephone leaned over and yelled in my ear.

I leaned back and nodded at her.

I felt the clamps holding us back disengage. We surged ahead, picking up speed as went, racing dizzyingly towards the end of the track that curved up into space. The wind whistled past my ears. I saw the end of the track come up and we fell.

From the personal journal of Hiram Maxim

“Green star,” said the gunnery sergeant, his gas mask hanging around his neck. “Prepare to fire!”

So it was. A lonely green star arced out from out forward positions. I scanned the skies for Persephone and Mr. Carver. Perhaps… In the distance, I could hear the rattle of my guns.

From the personal log of Lt Roger Carver, Royal Marines, HMS Thunder Child, 20 June 1897, 08:02 GMT:

We were flying! Somehow, we fell and staggered into the sky, lurching from one air current to the other. We started to rise. We were just as good as the Martians: we could fly too! As we rose above the roofless houses, I could make out the green star drifting above Horsell.

From the personal journal of Hiram Maxim

The cannon roared beside me. The shell exploded on the far side of the of the crater, kicking up piles of dust.

“Correct fire two degrees and you’ll have it,” I said to the gunnery sergeant. As the artilleryman barked the order to his crew, I heard a puttering noise overhead.

From the personal log of Lt Roger Carver, Royal Marines, HMS Thunder Child, 20 June 1897, 08:06 GMT:

We passed over the artillery position, some 80 feet below. I could see the men below wave excitedly to us, including Maxim. I definitely owed him an apology. Despite the life-and-death struggle we faced, I joined Persephone in grinning and waving madly to our comrades below.

The artillery resumed firing as we left them. I could see the shell land in the pit, but short of the tower. I could see our men in the trench line, supported by the machine gunners, firing into the pit, trying to prevent the Martians from gaining their fighting-machines.

We began a turn to starboard, so that our path would take us over the pit. I reached for one of the grenades, primed it by twisting the firing pin in the nose. I leaned over, released it. There was a satisfying sound of an explosion. I looked up: the tower was directly ahead.

“The tower!” I grabbed Persephone by the hand and pointed ahead. She nodded, throttling up the engine.

“Ulla! Ulla!” Suddenly, a fighting-machine reared up in front of us. The flying machine made a hard turn to port, as the Martian tried to bring its Heat Ray to bear on us.

I picked up a pair of grenades. I primed them and threw them at the Martian. They exploded harmlessly as they hit the carapace. I felt a flash of blistering heat behind me Persephone! I turned around. Persephone struggled with the tiller while the rudder of the aircraft burned.

From the personal journal of Hiram Maxim

“Ulla! Ulla!” The Martian fired its Heat Ray, shearing the tail off the flying machine. It spun in, trailing flame, crumpling as hit the ground. Persephone! Carver! The fighting-machine towered over it and raised a leg as if to crush them. I never felt so helpless.

I looked at the sergeant. He yelled at the gun crew, “Target that tripod! Two rounds, double-quick!” In short order, the artillery piece spoke twice. The first shell struck the fighting-machine, staggering it, while the second detonated as the machine collapsed.

I looked at the tower. It stood defiantly. “Get the tower!” I yelled.

The gunnery sergeant nodded. “You heard the man! Put fire on that tower. Make this one count!”

The gun fired. The shell exploded at the tower’s base. The tower titled and leaned at a drunken angle.

“Hit it again!”

“Sorry, sir,” said the sergeant, picking up his carbine. “That’s the last of our shells. From now on, it’s PBI.” He adjusted his gas mask.

“PBI?”

“Poor Bloody Infantry.” He motioned to his men. “C’mon lads.”

Persephone’s shotgun in hand, I followed.

From the personal log of Lt Roger Carver, Royal Marines, HMS Thunder Child, 20 June 1897, 08:20 GMT:

“Carver! Wake up!” I felt a hand shaking my shoulders. Slowly, I opened my eyes. I hurt in several places. Farmer knelt over me. Half his face was a mass of burnt red flesh, swollen, and cracked. Nonetheless, he smiled grotesquely when he saw me open my eyes. “I saw you crash.”

“Persephone?” I sat up.

“Still unconscious.” Farmer wheezed. “I’ve hidden her behind your craft’s wings. Amazing machine, really.” For a brief second, he was his old self, but only. “Your friends have managed to damage the tower, but it’s still standing.”

“We must destroy it.”

I looked around. Much of the pit looked like a scene out of Dante’s Inferno, consumed by smoke and fire. The wreckage of the Martian tripod lay toppled with smoke rising from its cracked carapace. Alarmingly, I saw a single unmoving grey tentacle dangling from the opening.

“Don’t worry,” Farmer laughed unevenly, looking at the tentacle. “He’s quite dead.” He helped me up and patted a canvas bag that hung over his side. “I took some of the explosives that the old man was working on in his lab. I needed your grenades, but here’s his gun.”

I took Maxim’s revolver, a big Webley from Farmer. It was still loaded. “You could’ve injured him seriously when you attacked him.”

“I had to do it, old man.” Farmer shrugged. “Fortunes of war and all that.”

I looked back where Persephone lay, safe for now. “Let’s go.”

From the personal journal of Hiram Maxim

We reached the trench-line overlooking the Martian pit. A number of our companions lay dead on the slope leading from the trench down into the enemy position, among them Lieutenant Mann.

“I told him to wait,” said Sergeant Howard, bitterly. He shook my hand. “He wouldn’t.”

“We’ve 19 men left, including your lot,” said Howard. “We saw your granddaughter and Mr. Carver go down in that craft of yours.” He shook his head. “Smoke’s too thick to see anything.” The machine gunners kept laying fire into the pit. “We’re trying to give them some cover.”

“The tower’s still up,” I said. The pins-and-needles feeling was not as strong. Did anyone else sense it? “It must be destroyed. I can’t order you to do it.”

“You don’t have to,” Howard smiled grimly. He turned to the men. “Fix bayonets and put on your gasmasks. We’ve a job to finish.”

From the personal log of Lt Roger Carver, Royal Marines, HMS Thunder Child, 20 June 1897, 08:42 GMT:

Farmer and I carefully moved along through crater, picking our way by the shattered remains of a low, spider-like machine with five metallic legs and two claw-like appendages in its front. I smiled. It looked like it had taken a direct hit from the 12-pounder. The thing was dead.

The tower, leaning broadly, stood in front of us, beside the open cylinder which was about the size of an apartment block. Suddenly our own gunfire which had been in the background, stopped. “Sounds like they’re about to storm the crater,” I said, looking at Farmer.

“The more the merrier!” Farmer laughed uproariously. We passed by the open maw of the cylinder. It looked like the mouth of an ancient monster. Yet, from inside, I could hear a small girl crying.

“Farmer!” I said, “Do you hear that?” The child’s sobbing echoed out of the dark.

“The child’s dead already,” said Farmer.

“She’s still alive!”

Farmer laughed. “You go save the bloody child, for all it matters. I’ll tend to the tower.” “Here, you’ll need these, old man.” He passed me two grenades. Then taking out a metal cylinder, he pushed a button on its lid. “I have this.”

I looked at Farmer. In a short time, he had changed irrevocably. Not just physically, but morally, spiritually. One way or another, we had all changed. For the better or worse, I didn’t know. We waved at each other. He went on his way; I went on mine.

I would not see him again.

Pistol drawn, I advanced into the open maw of the cylinder. “Hello?” I called out.

As I probed deeper, my eyes gradually became aware to the dim reddish light around me. This must be what daylight looks like on Mars. At the same time, I became aware of an overwhelming stench.

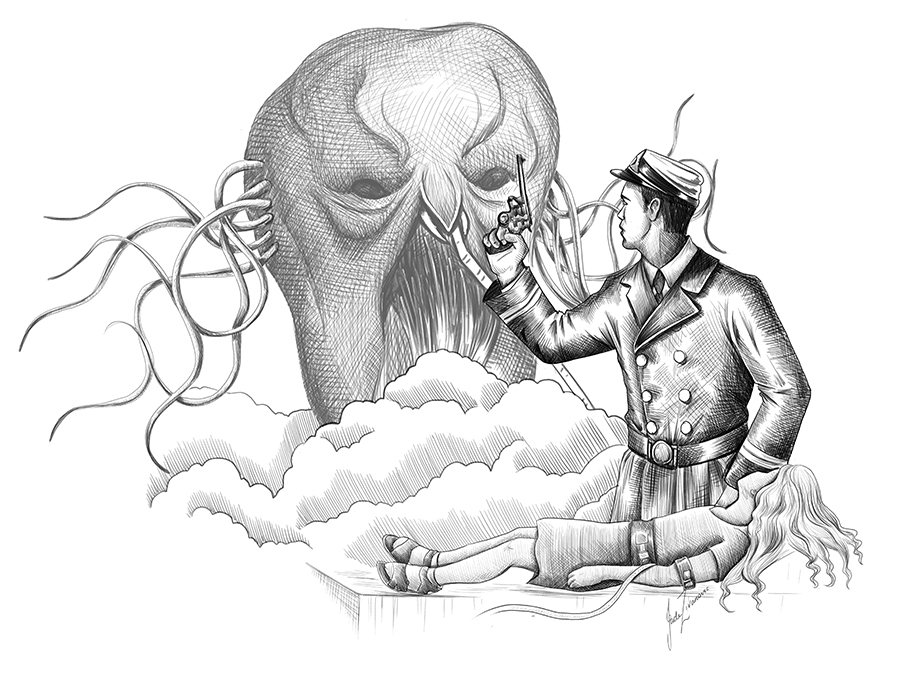

The cavern around me stank of rotting flesh. I repressed a shiver. God only knew what that meant. “Hello.” I called. “Hullo?” A small voice answered back. I stepped further in, pistol in hand. In the red gloom I could see a small blonde-haired girl in a ragged dress.

“Are you taking me home?” asked the girl. She was strapped down on something like the wrecked machine outside. A transparent tube ran from the machine’s innards to her arm. Every once in a while, the girl would groan and a pulse of red liquid would run from her into the machine.

They were milking her blood! “I most certainly am.” I stuck the Webley into my belt. I tried to grab the tube only be blocked by a metallic arm with a claw at the end of it, which darted in front of me. “I don’t think he’ll let you,” she said nodding to something behind me.

From the personal log of Lt Roger Carver, Royal Marines, HMS Thunder Child, 20 June 1897, 08:43 GMT:

“I don’t think he’ll let you,” the child said nodding to something behind me.

“He?” I spun around, pulling out my gun. It was then I saw my first Martian.

From the personal journal of Hiram Maxim:

Gripping Persephone’s shotgun, I advanced warily down the slope into the Martian pit, flanked by Sergeant Howard and his men, bayonets fixed. With the composition of the smoke below us uncertain, we thought it best to don our gas masks.

Howard ordered us forward with his hand. The rubberized fabric of the mask with its glass eye holes was claustrophobic, but as I detected no odour, I deduced that the masks worked. The band of smoke cleared, and I joined Howard and the others in removing the masks.

“We saw your machine land around here,” explained Howard as our skirmish line moved through a forest of ruined alien machinery. Soon, we came up the tangle of wings and tail surfaces that used to be my flying machine. I was elated to see Persephone standing beside them unharmed.

We embraced. “Grandfather,” she said, “when I came to behind the wing, Roger was gone.”

“The Commander clearly hid you there to protect you, while he moved on to the tower,” I surmised, quickly looking around us. “To where we must presently go.”

“Right,” said Howard. “Forward!”

From the personal log of Lt Roger Carver, Royal Marines, HMS Thunder Child, 20 June 1897, 09:02 GMT:

I beheld the Martian: a large greyish-brown misshapen head with pulsing veins and delicate whip-link tentacles protruding from its sides. Two tiny soulless beady black eyes regarded me impassively, set above a small beaklike mouth that sucked red fluid through a glass straw.

So this was one of the Master Race, one of the would-be conquers of Earth. I felt revulsed. But I also sensed something else. I was able to gather a series of impressions from the Martian. Telepathy? I sensed a brutal disdain for humanity, as we clearly didn’t matter to it.

I gripped my pistol. Yet I sensed something else. Something I sensed when I was on China Station and once cleared out an opium den. Confused satisfaction. Addiction! The Martians were addicted to human blood! I raised my pistol and squeezed the trigger.

The Martian reeled as the bullets struck its misshapen form. Anger directed at me filled my head, as the alien strained to rear its bulk against me, fighting earth’s gravity. I reached into my pocket and pulled out my two grenades. I twisted the two priming caps and threw them.

From the personal journal of Hiram Maxim:

We came across the open mouth of the cylinder when two explosions rang out from inside. A half-minute later, a figure carrying a small child staggard out.

“Roger!’ Persephone ran forward and embraced him, exchanging a quick kiss.

I followed, flanked by Howard and the men.

Carver gave the sobbing child to Persephone. “Take care of her, she’s been through a lot.”

I looked at the girl my granddaughter’s arms and then the cylinder. My curiosity surged. “Was she there? The Martians?’

“I could tell you more Maxim, but there’s no time. Farmer was here.”

“Farmer?”

“He went to the tower to destroy it. He’s quite mad. He has some of your explosives.”

I felt dread. “I knew he took it! A cylinder: small metal cylinder – did he have it with him?”

“Yes,” Carver nodded. “He did.”

My dread deepened. “Did he press a button on it?”

“Yes,” said Carver.

“We have to get out of here now.”

“What about the tower?” asked Howard, looking suddenly confused.

“Commander, Sergeant,” I’m afraid to say that tower is the least of our worries. If Mr. Farmer does what he intends, our concerns will be rendered academic…”

“Maxim,” I said, “make sense!”

“That cylinder – it’s a prototype of a new explosive I’ve been developing. I named after my daughter – Persephone’s mother – Carol… Carolinium. When that mad fool sets that bomb off, it’ll destroy everything in this pit.”

“What about the button?”

“He’s activated the delay timer. We have less than thirty minutes to escape!”

“Sergeant Howard,” I called out, with a rising sense of urgency, “Fall back.”

“You heard him,” Howard called to the men, “fall back – double time!”

We ran to the edge of the pit to a break in the smoke.

“Sir,” said Howard, eyeing the break in the smoke suspiciously, “we don’t have gas masks for everyone. Not including the little girl.” He reached for his mask. “Here, sir.” He took off his mask. “I’m an old man. Let the child have mine. I’ll take my chances with the smoke.”

“Keep your mask,” Sergeant,” I said, giving it back to him. “The child already has mine. Professor Maxim says the air should be clear enough if I go straight up the middle.”

“Aye, sir.” Howard saluted me. “Mind if I say, Mr. Carver, it’s been a pleasure serving with you.”

From the personal journal of Hiram Maxim:

As we charged up the slope, I was all too aware that Mr. Carver who had gallantly donated his mask to the little girl was the only one of us not wearing a mask. I prayed that my advice about staying the centre of the break would be enough.

I felt my boots dig into the sandy slope.

As we crested the rise, I checked over my shoulder through the smoke through the eyeholes in my mask. Mr. Carver was still there, his feet digging into the loose soil, but he seemed to be struggling.

From the personal log of Lt Roger Carver, Royal Marines, HMS Thunder Child, 20 June 1897, 09:17 GMT:

I tried to hold my breath as we ran up the slope. I stayed to the clearest path, where I could see a patch of blue sky. My lungs began to fill with acrid smoke. I stumbled, picked myself up and kept going.

I crested the hill but dropped to my knees again, coughing. I could not get up but immediately I felt myself being picked up and carried by Sergeant Howard. “It’ll be all right, sir. We’re clear of the pit and the smoke.”

“Thank you,” I felt myself croak. My chest was on fire.

We’d proceeded a hundred feet further when I heard Maxim yell for us to go to ground and cover our eyes. There was flash. The ground shook like it had been struck by a hammer. I managed to sit up in time to see black toadstool-shaped cloud, edged with fire, boil up from the pit.

I was sitting in the grass when Persephone joined me, still holding the girl. “Oh Roger.” She hugged me. “Are the Martians…”

“…quite dead – at least here anyway,” I took her hand. I watched the reddish black cloud rise skyward. “I shall never doubt your grandfather again.”

I lost consciousness.

Returning to the Underground, I see the Martian’s red weed has covered the Thames.

On the 12th day of his imprisonment Well’s throat is so painful that, taking the chance of alarming the Martians, he attacks the creaking rain-water pump that stands by the sink, and gets a couple of glassfuls of blackened and tainted rain-water.

@NUWSS outposts in regular contact now. #Thanks to @SirJohnTheEngineer and his #Wireless marvel. He says thank @GMarconiWireless

Thank you @GMarconiWireless

Getting harder to move through #London #RedWeed is everywhere #Thames is now beginning to break banks in places. What will become of #London?

The stench of the dead from the #BlackSmoke is getting worse. #GasMasks have more than one purpose now.

The Martians still have a large encampment near Hampstead. It’s like a great city, and at night, the sky is bright with their lights.